1,500 Migrants Are Sleeping at Chicago Police Stations as Winter Approaches

Wicked problems and the policeman who killed Jacob Riis's dog, 1870

Hi, I’m Alison Peck and this is How We Got Here, a journey through the history of United States immigration law with bulletins from the front lines of today, by a law professor and immigration lawyer.

If you’re not already a subscriber and would like to receive these weekly emails, you can subscribe here.

My brother, who lives in Chicago, tells me that he’s seeing things he’s never seen before: groups of immigrants, often families with young children, living on the streets. Last month, the Chicago Sun-Times reported that 13,500 migrants have arrived in Chicago since last year. Nearly 1,600 people are sleeping in and around police stations while the City of Chicago prepares tents, which they call “winterized base camps,” for winter housing.

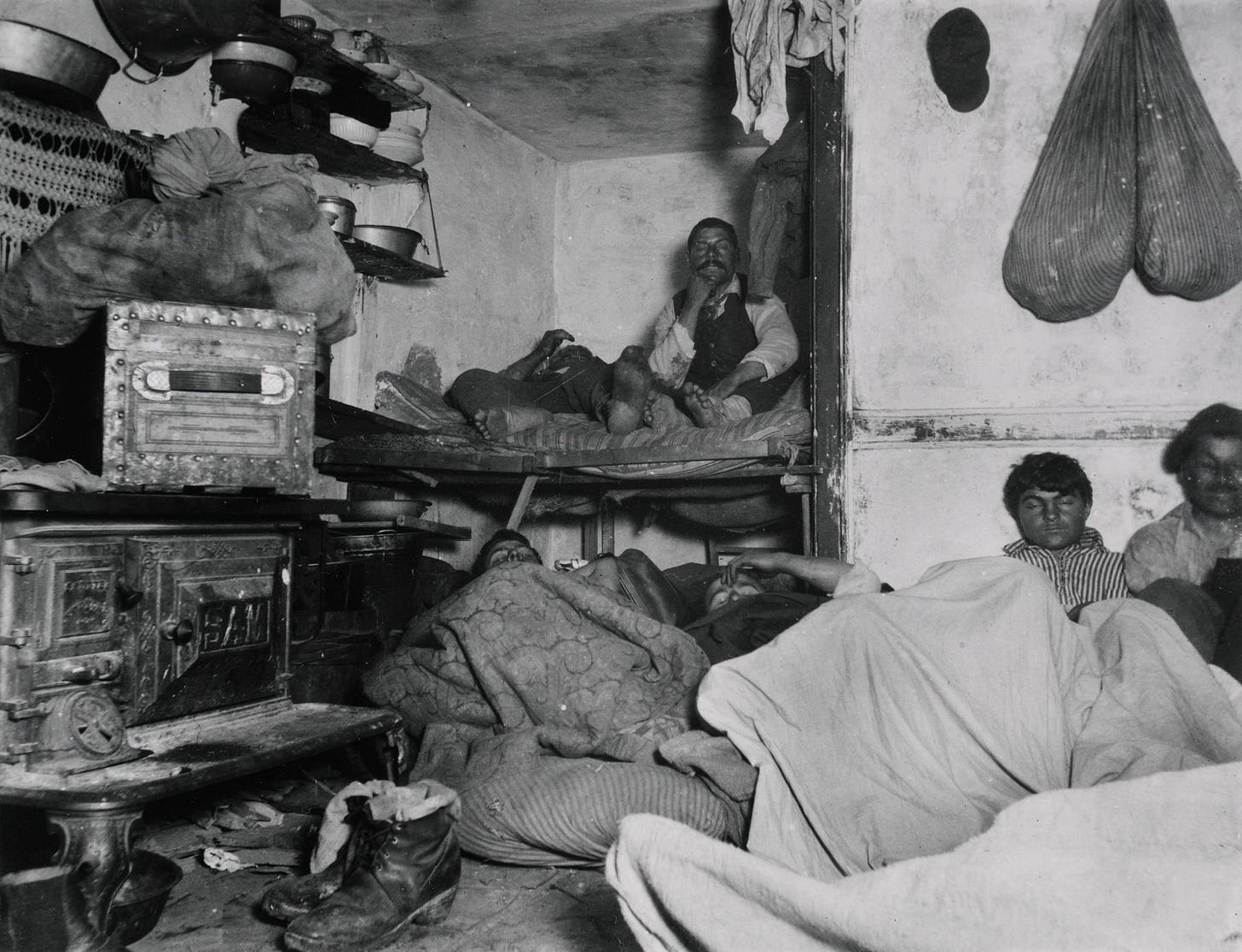

Reading about an immigrant wave living on the streets and sleeping in police stations reminded me of the story of the police department security guard who killed Jacob Riis’s dog. Riis immigrated to the United States from Denmark in 1870, like hundreds of thousands of others seeking opportunity in the postwar boom. He is best known for his work illustrating the conditions of the New York City tenements in his 1890 book, How the Other Half Lives.

Maybe you’re familiar with the story about Riis’s dog, because Riis told it to his good friend Theodore Roosevelt. But odds are, like me, you’ve never read it before. With history repeating itself on the streets of Chicago, New York, D.C., and other cities, this might be a good time to remember.

Jacob Riis: Immigrant, Journalist, Photographer, Social Reformer

After arriving in the U.S. in the spring of 1870, Riis found work in carpentry and mining, but soon the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Mad about the Prussian seizure of Schleswig from Denmark six years earlier, Riis spent all his money traveling to ports from which he hoped to volunteer for France, but each time he was rejected. He wound up penniless, homeless, and “too shabby to get work, even if there had been any to get,” Riis wrote in his 1901 autobiography, The Making of an American.

On a cold, rainy October night, Riis found himself alone by the Hudson River (which he called by the old Dutch name, “North River”). Without food, shelter, or prospects, the river’s strong current tempted him. “Would they miss me much or long at home if no word came from me?” he wondered. “Perhaps they might never hear.” He edged closer to the river’s edge. “And even then the help came,” he recalled.

A wet and shivering body was pressed against mine, and I felt rather than heard a piteous whine in my ear. It was my companion in misery, a little outcast black-and-tan, afflicted with fits, that had shared the shelter of a friendly doorway with me one cold night and had clung to me ever since with a loyal affection that was the one bright spot in my hard life. As my hand stole mechanically down to caress it, it crept upon my knees and licked my face, as if it meant to tell me that there was one who understood; that I was not alone. And the love of the faithful little beast thawed the icicles in my heart. I picked it up in my arms and fled from the tempter; fled to where there were lights and men moving, if they cared less for me than I for them—anywhere so that I saw and heard the river no more.

In the midnight hour we walked into the Church Street police station and asked for lodging. The rain was still pouring in torrents. The sergeant spied the dog under my tattered coat and gruffly told me to put it out, if I wanted to sleep there. I pleaded for it in vain. There was no choice. To stay in the street was to perish. So I left my dog out on the stoop, where it curled up to wait for me. Poor little friend! It was its last watch.

In the police station crowded with homeless men, a German loudly carried on about the war in Europe, and Riis rose to the fight. An Irishman egged them on. In the morning, Riis woke to find someone had stolen a gold locket with a lock of hair from his beloved in Denmark. He complained to a policeman, who called him a liar and a thief. The policeman – whom Riis believed was German – said he had heard Riis arguing for France the night before. Riis lit into the officer (he could not even remember later what he had said), and the officer told the doorman to put him out.

My dog had been waiting, never taking its eyes off the door, until I should come out. When it saw me in the grasp of the doorman, it fell upon him at once, fastening its teeth in his leg. He let go of me with a yell of pain, seized the poor little beast by the legs, and beat its brains out against the stone steps.

At the sight a blind rage seized me. Raving like a madman, I stormed the police station with paving-stones from the gutter. The fury of my onset frightened even the sergeant, who saw, perhaps, that he had gone too far, and he called two policemen to disarm and conduct me out of the precinct anywhere so that he got rid of me. They marched me to the nearest ferry and turned me loose. The ferry-master halted me. I had no money, but I gave him a silk handkerchief, the last thing about me that had any value, and for that he let me cross to Jersey City. I shook the dust of New York from my feet, vowing that I would never return.

Of course, he did return. The incident enkindled in Riis a desire to reform the slums, which stayed with him after his fortunes improved. The memory, he said, guided his future work.

Humans and Animals

I write these posts on Friday or Saturday mornings from my home office, a converted bedroom in our house. My companion at these writing sessions, without fail, is a tabby-on-white Domestic Short Hair cat named Artemis. Artie is nearly sixteen years old now, and she spends most of her time napping (and snoring) on a burgundy-velvet upholstered armchair a few feet to my right. I’ve placed a fleece pullover I’ve recently worn on the seat and positioned a small Shaker wood stool in front of the armchair so she can climb up and down without assistance despite arthritis. Occasionally she wakes up and chirps at me, often because I have been muttering something to myself out loud – reminding me, I think, to reestablish consciousness. A few times a day she gets up, walks over to my feet, and meows until I pick her up (because she is, after all, a cat).

One might respond that Riis’s story of cruelty to an animal ought to compel us less than the stories of cruelty to human beings we see every day on the news. And I’d agree. As I practice immigration law and read immigration history, I come across many sickening stories of cruelty to human beings. But reproduction of graphic accounts of those horrors feels gratuitous without a strong contextual reason for including them.

This account of cruelty to an animal, while horrible, can bear to be repeated, and it strikes a compelling chord with many people. I’ve never experienced the thin margin of survival that Riis and many other immigrants have known, but I’ve known moments of deep loneliness when only an animal offered comfort. Many people know that feeling – so many that Riis’s story became iconic in the annals of civic reform. As the United States faces the humanitarian crisis of another immigration wave, maybe the story bears repeating again.