After the Democratically-controlled Senate and the Biden administration put forth an immigration reform bill this winter, House Speaker Mike Johnson announced it “dead on arrival” in the Republican-controlled House. Donald Trump called the bill a “Death Wish” for the Republican party, while Democrats claimed Trump opposed the bill because it would give the Biden administration a win going into the 2024 presidential elections.

Migration and politics are so intertwined that it can be hard to tease out truth from propaganda. As I sort through the records of migrations past, I’m facing the same issue.

The third great-grandfather of my biographical subject, former assistant secretary of State Wilbur J. Carr, emigrated from the Duchy of Württemberg in 1737. For several decades prior, people had been leaving southwest Germany by the thousands for the British colonies of North America. Before the American Revolutionary War finally put a halt to emigration (for a while), around 111,000 Germans would travel up the Rhine, board ships in the Netherlands and – after a stopover in England (often at the Isle of Wight) to board a British vessel that could legally transport passengers to the colonies – set sail for North America.

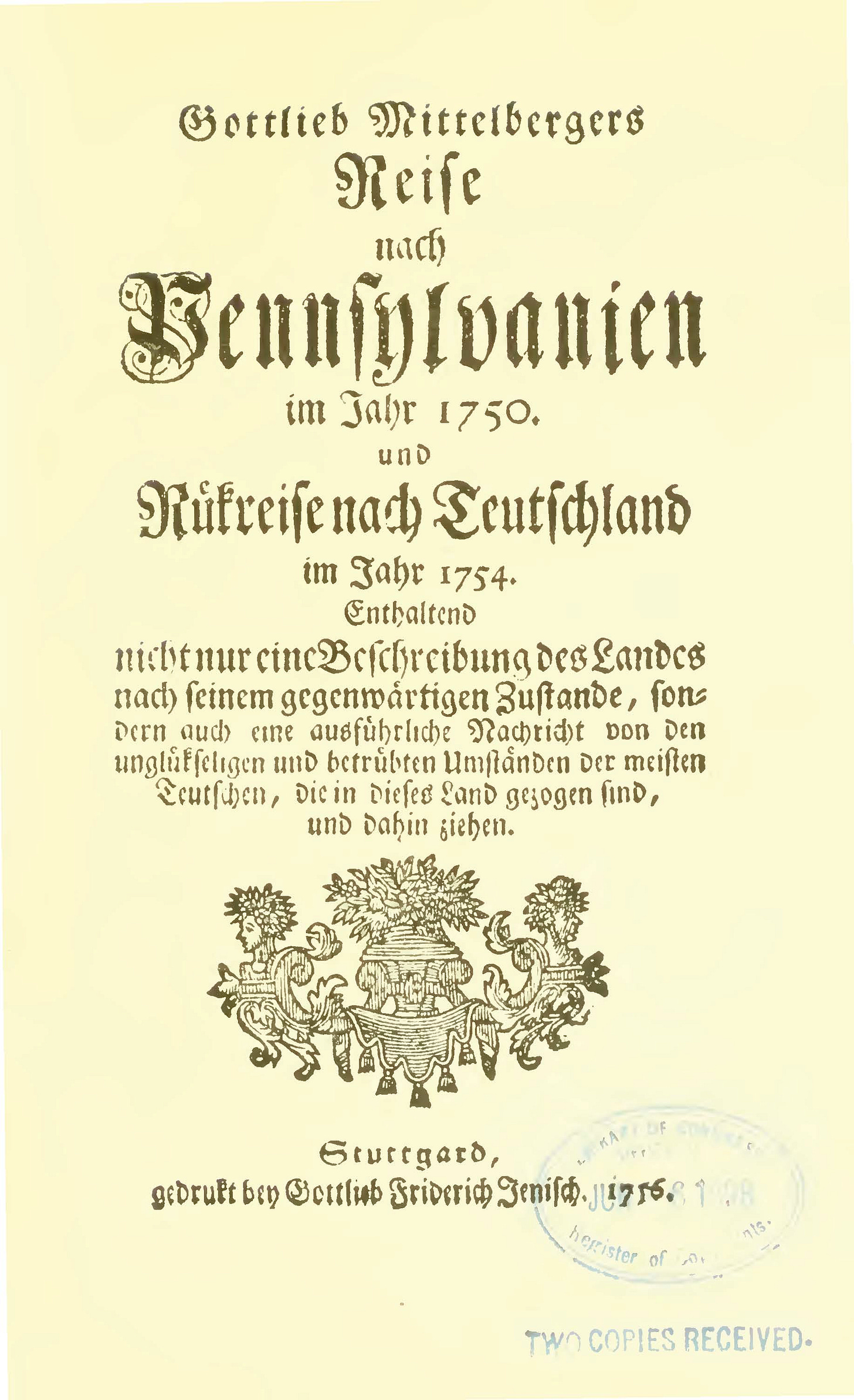

Gottlieb Mittelberger’s Journey to Pennsylvania

In 1756, a Württemberg church organist named Gottlieb Mittelberger published an account of the perils of such a trip in a book called Journey to Pennsylvania in the Year 1750 and Return to Germany in the Year 1754. Gottlieb described the trans-Atlantic passage as a veritable hell on earth. Having consumed most of their rations during the inevitable delays of the weeks- or months-long trip up the Rhine and through the Netherlands, Mittelberger wrote, passengers often faced nothing but starvation, disease, and death on the ocean voyage:

[D]uring the voyage there is on board these ships terrible misery, stench, fumes, horror, vomiting, many kinds of sea-sickness, fever, dysentery, headache, heat, constipation, boils, scurvy, cancer, mouth-rot, and the like, all of which come from old and sharply salted food and meat, also from very bad and foul water, so that many die miserably.

Add to this want of provisions, hunger, thirst, frost, heat, dampness, anxiety, want, afflictions and lamentations, together with other trouble, as c.v. the lice abound so frightfully, especially on sick people, that they can be scraped off the body.

Conditions are so crowded, Mittelberger reported, that illness is inevitable; the dead lie in bunks next to the living. Among pregnant women, “[f[ew of this class escape with their lives”; and “[c]hildren from 1 to 7 years rarely survive the voyage; and many a time parents are compelled to see their children miserably suffer and die from hunger, thirst and sickness, and then to see them cast into the water.” On his voyage, he said, thirty-two children died and were thrown overboard, their parents suffering all the more because “their children find no resting-place in the earth.”

Upon arrival, for those who managed to survive, things were little better. The many who could not afford to pay the debt for their passage were sold into indenture. Children under five years old cannot be brought with the parents but “must be given to somebody without compensation to be brought up, and they must serve for their bringing up till they are 21 years old.” Many parents never see their children again. Much worse, to this church musician and his readers, was knowing that these children would often be delivered into the hands of godless Americans and grow up outside the church:

For there are many doctrines of faith and sects in Pennsylvania which cannot all be enumerated, because many a one will not confess to what faith he belongs.

Besides, there are many hundreds of adult persons who have not been and do not even wish to be baptized. There are many who think nothing of the sacraments and the Holy Bible, nor even of God and his word. Many do not even believe that there is a true God and a devil, a heaven and a hell, salvation and damnation, a resurrection of the dead, a judgment and an eternal life; they believe that all one can see is natural. For in Pennsylvania every one many not only believe what he will, but he may even say it freely and openly.

But one begins to guess at Mittelberger’s motives when he describes the misanthropy and misery among even the healthy on board the miserable ships:

One always reproaches the other with having persuaded him to undertake the journey. Frequently children cry out against their parents, husbands against their wives and wives against their husband, brothers and sisters, friends and acquaintances against each other. But most against the [traffickers].

Many sigh and cry: “Oh, that I were at home again, and if I had to lie in my pig-sty!” Or they say: “O God, if I only had a piece of good bread, or a good fresh drop of water.” Many people whimper, sigh and cry piteously for their homes; most of them get home-sick. Many hundred people necessarily die and perish in such misery, and must be cast into the sea, which drives their relatives, or those who persuaded them to undertake the journey, to such despair that it is almost impossible to pacify and console them.

This rant on emigration to America and subsequent settlement in Pennsylvania continues for 144 pages. Laws are unjust; women are beautiful but too refined to work; even the richness of the land is a curse, for “this beautiful country, which is already extensively settled and inhabited by rich people, has excited the covetousness of France,” which had recently commenced raiding, and Pennsylvania “cannot long stand a war,” especially since the Quakers would be useless in one (yes, he says that, in so many words).

The Politics of Württemberg, 1750s

Such a diatribe, after a hundred pages or so, passes from horrifying to almost laughable to modern ears, and it’s hard to say what, if any, effect it had on prospective German emigrants in the eighteenth century. Although German emigration did subside dramatically from 1756 to 1762, that period marks the Seven Years War, the Prussians and British against an Austrian and French alliance joined by Saxony, Sweden, Russia, and Spain. The French and Indian War between the British and French in North America (alluded to by Mittelberger) was but one theater of the war that engulfed Europe.

Mittelberger’s publication cannot be separated from the political aims of the Duke of Württemberg at the time, Carl Eugen. Mittelberger’s book begins with a dedication to the Duke: “To the Most Illustrious Prince and Lord, CARL, Duke of Württemberg and Teck, Count of Mömpelgardt, Lord of Heidenheim and Justingen, etc., Knight of the Golden Fleece, and Field-Marshal-General of the Laudable Swabian Circle, Etc. To My Most Gracious Prince and Lord.” (To contemporary American ears this sounds like nothing so much as a Monty Python skit, but at the time it indicated fealty.)

Duke Carl Eugen found himself in a tight spot – and emigration to the Americas wasn’t helping. As a medium-sized (and Protestant) principality sandwiched between (Catholic) Austria and France, Württemberg had been trampled by the warring Bourbons and Habsburgs for two centuries. Now alliances had shifted, as France and Austria joined forces against the militant (and German, and Protestant) Prussia. For smaller states in strategic locations like Württemberg, survival meant cultivating the right friends in the most delicate of positions.

Duke Carl Eugen needed not only diplomatic protection but money to maintain or increase his political power and position within the balance of the Holy Roman Empire, and larger powers could provide funds. In return, those powers wanted the only thing Württemberg could offer in any volume: people, specifically soldiers. Feeling pressured but geographically remote from Prussia on the one hand, and squeezed between nearby France and Austria on the other, the duke had cast his lot by 1752: He entered into a subsidy contract with France, promising to deliver 3,000 soldiers. And he was coming up short.

In addition to units provided to other sovereigns under subsidy treaties, Württemberg also maintained an army to support the Swabian Kreis, to which it belonged, and one to protect itself. Historians differ as to the level of voluntariness, respectability, and desirability of the soldier profession among the peasants most often recruited (and sometimes conscripted) into its ranks. Some soldiers may have viewed it as oppression, others as a viable and honorable career option. For minor nobles with little inheritance, the officer corps offered a more dignified career than poverty. (For more on this subject, I can’t recommend Peter H. Wilson’s book, War, State, and Society in Württemberg, 1677-1793, highly enough.)

Regardless of its popularity, however, the military and the soldier trade were critical to the survival of medium-sized states like Württemberg – and watching thousands of eligible young men pack up and head down the Rhine must have unnerved Carl Eugen. Whether he encouraged or simply permitted Mittelberger to publish his work, it undoubtedly would have appeared politically useful to the duke. According to Wokeck, a large number of the “letters home” from emigrants surviving in German collections served as anti-emigrant propaganda and cannot be relied upon to accurately represent the emigrant experience. Mittelberger’s account certainly reads like a more extended form of PR to discourage emigration.

Fact Checking Mittelberger

The horrors that Mittelberger described did occur during emigration, and much more frequently than one would want to imagine. But Mittelberger overstates the case when he suggests that these horrors befell nearly everyone on nearly every voyage. At the other extreme, emigrant Peter Sauer reflected, “The ship voyage is as one takes it. For my part, I maintain that it is a comfortable trip if one carries along victuals to which one is accustomed and controls one’s imagination.” Most voyages probably feel somewhere between these extremes.

In her painstaking book Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America, Marianne S. Wokeck surveys reports of mortality rates on German emigrant ships. Between 1727 and 1805, one source estimates overall mortality at 3.8 percent (roughly four and half times the three-month crude death rate for many places in Germany in the mid eighteenth century, but nowhere near what Mittelberger’s account would have one believe). Other voyages, especially group voyages with better planning and provisions, had mortality rates as low as 0.13 to 1.6 percent, compared with a death rate of 0.8 percent in five German communities in that century. Death rates were, as Mittelberger stated, higher among young children, who were more vulnerable to disease. While these risks certainly would have merited very sober consideration by any prospective emigrant, they don’t approach the apocalyptic proportions that Mittelberger suggested.

Separating Politics from Fact

We will never know all the true facts about emigration in the eighteenth century (or today). But we can remember that migration and politics have always been, and will likely always remain, intertwined. Reading between the lines has been and continues to be important.