William F. Allen had a problem. As secretary of the American Railway Association, Allen’s duties beginning in 1872 had involved editing the Official Railway Guide. The Guide proposed to publish the schedules of all major railways for use by railroad personnel, ticket agents, and corporations, but it had one major obstacle: At the time, at least fifty separate time standards existed in the United States. How could a shipper, passenger, or railroad executive make firm plans when the 3:59 arrival from St. Louis might actually pull into the station two minutes later than the 4:07 departure for Topeka? Something had to be done.

Railroad executives had been meeting since shortly after the Civil War to sort this out. Their first associations literally named the problem: “The General Time Convention” and “The Southern Railway Time Convention” eventually merged to form the American Railway Association, but previous efforts to standardize schedules had failed. The principal of a women’s seminary in Saratoga, New York, named Charles F. Dowd had hit on the principle of using meridians one hour apart as a time standard, and several other influential thinkers, including Harvard mathematician Benjamin Peirce, had arrived at the same conclusion. Though Dowd lobbied persistently for the adoption of his ideas, the details proved too complicated for widespread concurrence.

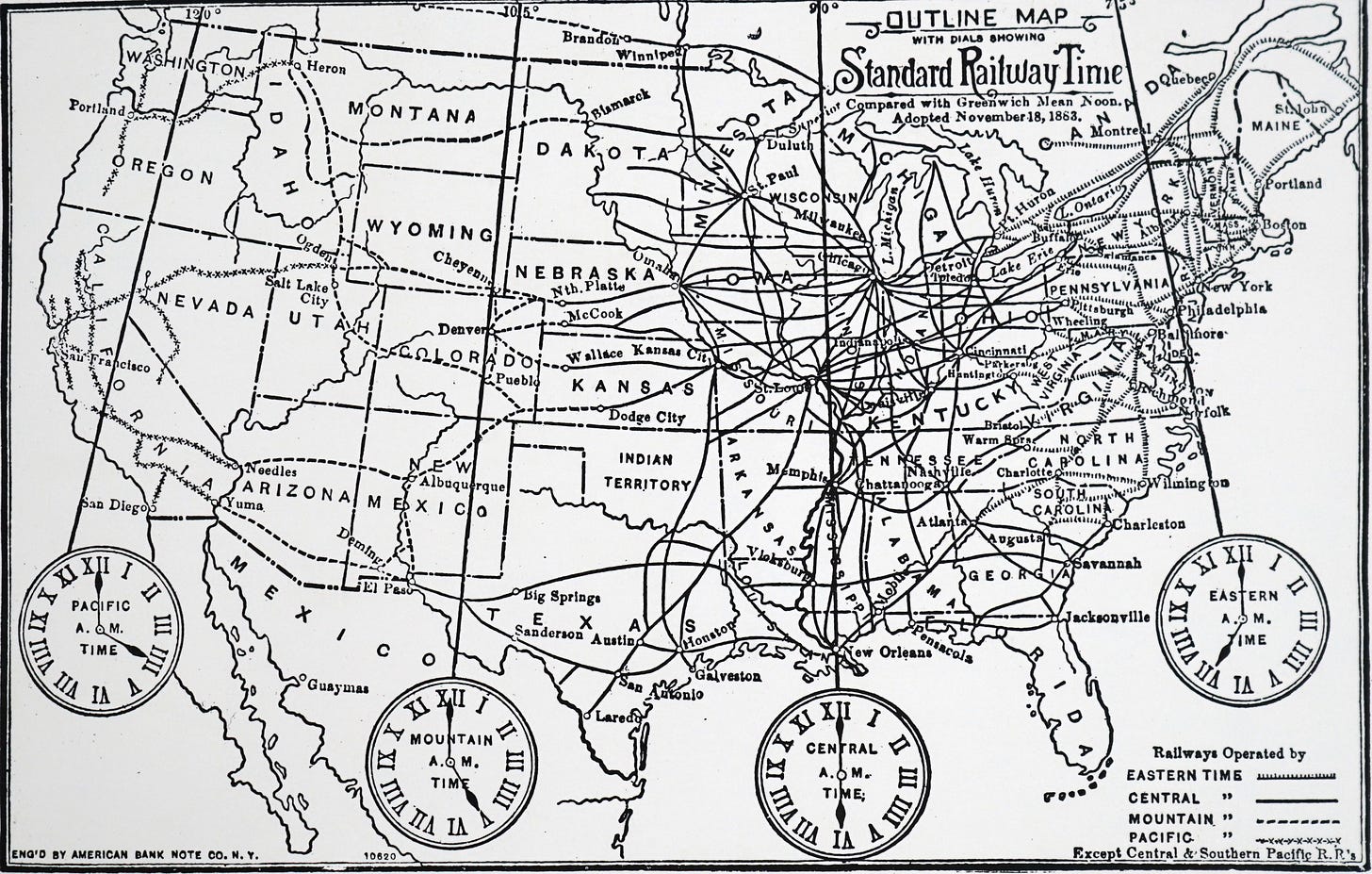

In April 1883, Allen proposed a simpler system, also using meridians but along more flexible axes, and with a coordinated system for implementation. By adopting Greenwich Mean Time (already at use in England) as the starting point, he encouraged his system’s adoption across Europe as well as the United States. By October 1883, Allen had obtained the consent of the principals of 78,000 miles of railroad, the Naval Observatory, and the Cambridge Observatory. With the railroads acting in concert, many mayors soon concurred, eliminating the need to maintain a system of local times. On November 13, 1883, at precisely noon on the 90th meridian according to the Alleghany Observatory, fifty different standards of time in America resolved into four.

Standard Time in American Life

I stumbled across this history of standard time while researching the dramatic changes in daily life for people coming of age in the late 19th century. I found a curious little volume, published by Allen but circulated only privately, Standard Time in North America, 1883-1903, complete with an original letter from Allen to Messrs. Luther Tucker & Son of Albany, New York, sharing with them this short history but asking that it not be mentioned in their “valuable publication.” After a brief recitation of the facts above, the volume reprinted more than fifty letters from railways executives confirming Allen’s assertion that he, not Dowd, deserved credit for the system as adopted. (Apparently authorship was in some dispute.)

For the people of southern Highland County, the Ohio farm community I’ve been researching for a biography of State Department official Wilbur J. Carr, Standard Time made life a little simpler. In 1877-78 they had organized and built a narrow gauge railway connecting their community to lines running to Cincinnati and Columbus, meaning better price margins on stock and produce without the land transport to the county seat. Though the era of mass emigration to the western territories had reached its peak a few years earlier, passenger trains would now connect more reliably in neighboring cities too, making regional travel for business or pleasure more accessible. Church and school bells gradually waned in importance as people lived more by clock time.

The Long Tail of the Railroad Revolution

As a lawyer, I tend to expect movements as dramatic as standardizing time across the country to proceed from government policies. It startled me to learn that Washington had nothing to do with Standard Time; one private industry – albeit one so dominant as to have practically captured the federal government before the turn of the century – changed the lives of millions of people, just by deciding to.

In effect, the railroad industry did to time what industrialists already had done to material: They owned it, routinized it, and repackaged it for public consumption. This effect, which Alan Trachtenberg called “The Incorporation of America,” radically changed one thing in Highland County: the prospects of their sons who left the farm.

For generations before, Americans raised on the farm could either farm, or perhaps apprentice and learn a trade, or a profession like law or medicine. As corporations changed American life, they also created a new class of people, the managers who kept the trains running on time (literally and figuratively).

The Managerial Class in Washington

Those managers landed not only in private industry but, increasingly, in government as well. Wilbur Carr attended business college and obtained his first position as secretary to the headmaster of a military school in Peekskill, New York. Attracted by the growing professional class in Washington, D.C., however, he took the civil service exam and won a job as a State Department clerk in 1892.

The year before Carr arrived in Washington, Congress passed a new immigration law to deal with the administrative problems created by the entry restrictions they had imposed a decade earlier. Someone had to determine whether an arriving passenger should be excluded based on disease, disability, or criminal history, and Congress had now learned that someone had to review those decisions (whether entry or exclusion) for reliability . New “boards of special inquiry” inherited the responsibility to conduct that review.

By 1891, the basic elements of what we now call “the immigration courts” were established. Future immigration restrictions that Carr would profoundly affect, such as the national origins quota system of the 1924 Immigration Act, would require even more extensive administrative implementation and oversight. Carr – the kind of person so reliable you could set the nation’s watches by him – gradually took over many such administrative tasks for the State Department.

The Un-incorporation of America in the 21st Century

The 21st century may see the loosening of the hegemony of the corporation in American life. While major corporations like Apple, Google, and Amazon still wield massive and disruptive power, other traditional industries – like, for example, higher education – face disruption from the ground up. The internet has concentrated power in a few areas but also democratized access and opportunity for millions (or billions) of people. This semester, I’m teaching a novel course called Entrepreneurship for Lawyers to give our law students some fundamental skills to capitalize on that democratization and to shape their careers and the legal profession in the ways they want to see.

Walking in the shoes of Carr through the late 19th century has convinced me how powerfully the technological revolutions of his era made immigration restriction both necessary (in many people’s eyes) and possible. I suspect the technological revolutions of our era will transform immigration law far, far more than will any quota, amnesty, or border wall currently percolating in the minds of Washington bureaucrats. We’ll find the future of immigration policy by imagining life disrupted by technology for people all over the world.