This is How We Got Here, a walk through our immigration policy past with updates from the front lines – and, recently, some thinking about where immigration might be going in the near future.

.AI, Immigration, and “Speciesism”

Just as I’ve been thinking a lot about AI and its scary potential to displace human social control of the world, I came across this quote:

“Is there, indeed, a danger that the race which has made our country great will pass away, and that the ideals and institutions which it has cherished will also pass?”

These are the words of Prescott Hall, co-founder and chief advocate of the Immigration Restriction League. From its founding in 1894, the IRL worked ardently for a quarter century to stop immigration. In 1924, it succeeded (for a while).

Contemplating AI, Hall’s words from 1912 raise new questions.

Hall, of course, wanted to preserve the control of certain groups of humans over others. Current fears, in contrast, center around preserving the control of humans over a “new digital species” created by humans.

Is it different?

If you think so, does the answer change if AI eventually develops an awareness of its own existence and a fear of being annihilated, as some of its own creators warn it will? If that happens, how would an “AI Restriction League” be different from Hall’s group? Wouldn’t it be “speciesist,” in Peter Singer’s terms, to suppress AI to maintain our “cherished” institutions?

We might even find ourselves sounding a bit like Prescott Hall – worried, fretting, that this new “race” (to use his term) might overrun us, destroying everything of value that we’ve created, perhaps even destroying us. Sounding unnervingly 21st century, Hall wrote,

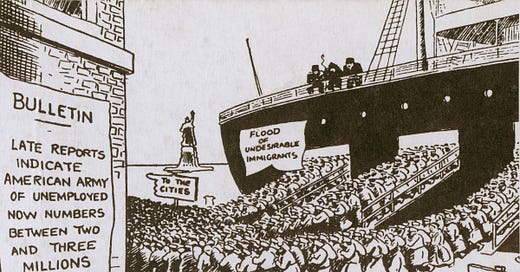

“Americans have hitherto paid very little attention to this [immigration] question: first, because they have not considered the difference between hostile and peaceful invasions in history; and second, because they fail to observe that recent immigration is of an entirely different kind from that which our fathers knew. … If the million people coming every year came not as peaceful travelers, but as an invading hostile army, public opinion would be very different to what it is; and yet history shows that it has usually been the peaceful migrations and not the conquering armies which have undermined and changed the institutions of peoples.”

Once technology sets a trend in motion, however, humans may not be able to stop it. Hall worried about the effects of rapid technological change (again, using language that evokes objections to the immigration waves of today):

“Formerly, America was a hard place to get to, and a hard life awaited those who came, although the free and fertile land offered rich prizes to those with the energy to grasp them. To-day, the steamship agent is in every little town in Europe; fast steamers can bring thousands in a few days, and wages, often indeed not enough for an American to live decently on, but large in the eyes of the poor European peasants, await the immigrant on landing. There is, moreover, abundant testimony to the fact that much of the present immigration is not even a normal flow of population, but is artificially stimulated in every possible way by the transportation companies which have many millions invested in the traffic.”

The technology of change may be different this time — radically different — but the process is the same. Man innovates. Society changes. People move. Control shifts. Repeat.

At some point, perhaps the innovation creates a quantum leap of change. How big does the leap have to be before we’re allowed to try to stop it?

The Messiness of Moral Responsibility

Two weeks ago, I wrote about Jan Karski, who heralded the Holocaust to Western leaders. Karski’s story evoked questions about individual moral responsibility — not for the evils we create, but for those we encounter.

In response, a colleague shared this article about an intriguing civil rights exhibit at Temple Beth El in Birmingham, Alabama. The exhibit explores a Jewish perspective on the civil rights movement as a way of encouraging activism today and strengthening bridges between communities.

The New York Times article begins by exploring the story of one Birmingham merchant, Emil Hess (owner of the Parisians department store in Birmingham during the civil rights era (and a relative of my colleague). Faced with competing protests by Black activists and resistant whites, Hess made a decision: He integrated his store and later became one of the first white merchants in Birmingham to hire Black salespeople.

The Times article, like the exhibit, asked hard questions about Hess’s actions: “Did he have a genuine desire for fairness? Did he simply fear a boycott? Or did his intentions even matter?”

We might dig one layer deeper: What if Hess did desire equality, but did not act until the threat of boycotts forced his hand? Was he different than those whose livelihoods were not directly threatened and chose to remain on the sidelines? Can we even know what “heroism” means if we are not forced to act?

The curators of the exhibit told the Times that they strove to raise these types of questions.

‘“Rather than judging history between the good and the bad, or assuming we would have been on the right side,’” the synagogue’s director of programming told the Times, “‘what can we learn by taking a more nuanced look at understanding how people responded with the resources they had?’”

Carr, State, and Moral Failure

These same questions drove me to write a book about a mid-level civil servant at State who failed to stand up to State’s bureaucratic indifference to Jews trying to flee the Nazi regime.

Wilbur J. Carr’s job, as the top administrative secretary of the Department, was mostly to make sure State policies got implemented smoothly: budgets, personnel, facilities, that type of thing. That doesn’t mean he lacked power. He had a seat at the table when decisions were made whether to grant visas to German and Austrian Jews, and he implemented State policy. The vast majority of available visas went unused; hundreds of thousands of people could have been saved.

This week, I’ve been re-reading a 1960 biography of Carr, Mr. Carr of State. The book, commissioned by Carr’s widow, is largely hagiography, but its author, Katharine Crane, had access to people who had worked with Carr in Washington or as consuls. While their recollections reveal only one (flattering) side of Carr, they do include anecdotes that suggest a complex story.

Colleagues repeatedly described him as “warm” or “kind” beneath a formal demeanor. One Foreign Service officer, Donald Dunham, later wrote a book about his experiences in the Service. Since he never knew Carr well and wrote for an unrelated purpose after Carr’s death, the story may be reliable.

In the early days of consular appointment on merit rather than patronage – a reform that Carr had labored to achieve and considered his signature achievement – candidates had to pass an exacting written test followed by an oral examination. Dunham had failed the written test by less than a point; his success rested on impressing the examining board, and he was terrified.

Dunham came before the examining board on a hot Saturday afternoon in May 1931. He sat nervously in his chair; six examiners sat in a semicircle across from him. They had already interviewed seventy-eight candidates that week. He was the second from last.

One examiner asked innumerable questions about biographical details that were readily apparent from Dunham’s resume.

Suddenly, another examiner asked, “‘Why do you want to enter the Foreign Service, Mr. Dunham?’”

Dunham was dumbstruck. He’d been prepared to discuss national politics and international relations, but not his own personal motivations.

“‘I beg your pardon sir,’” Dunham stumbled.

“‘I asked why you want to enter the Service.’”

Dunham struggled for a moment to think of an authentic response that these impatient examiners would find acceptable.

“‘Do you find that a difficult question to answer, Mr. Dunham?’”

He did, in fact. So he simply told the truth. “‘I want to meet and get to know people all over the world.’”

No one commented. His file was passed to the last man in the semicircle, whom Dunham identified as “the Foreign Service Chief of Personnel.” Crane confirmed that the man was Carr, whose duties as assistant secretary in 1931 included personnel management of the Foreign Service.

Dunham felt a shift in tone as Carr spoke. “He was a genial man and spoke quietly,” Dunham said. “I relaxed a bit at the sound of his voice.”

“‘Don’t be embarrassed about wanting to enter the Service to meet people,’” Carr told him. “‘That’s a large part of your trade, in fact in that lies the secret of success in the Service. … Let me give you a piece of advice. Hold on to that reason wherever you are, whatever your job is. Don’t worry about how different other people may look to you or how differently they may live. Keep an open mind and be natural and you will get along fine. And – you will have a good time in the bargain.’”

This single anecdote does not, of course, tell the story of Carr’s character. One may be kind toward some people and unfeeling toward others, or may counsel open-mindedness while harboring prejudice. But these stories, and others like them, complicate my assessment of Carr’s actions – and his inactions – as assistant secretary in a Department that blocked immigration for four decades and ignored or obscured the Holocaust. It’s hard to simply write him off as evil or unfeeling.

What It Meant to Be Human

The messiness of this story holds my attention as I read it day after day. But after other projects prompted me to dive deeper into AI research, I experienced conflicting emotions.

Why study our immigration past when the present, and everything that proceeded it, is likely to become obsolete within our lifetime?

Even as I asked the question, I knew I couldn’t get off the hook that easily. Perhaps more than ever, we face profound existential questions about what it means to be human. As the boundary between human and machine rapidly blurs, what will it mean that “all men are created equal”?

Faced with these questions, perhaps we might start by studying what it meant to be human, in all its messiness.