When Queen Anne “Bussed” German Migrants to America

Transporting migrants for political gain is nearly as old as Philadelphia

From messengers promising gold and riches, they heard the stories of America. The government, they heard, was welcoming migrants with open arms. Work was plentiful and workers were needed. A few who had gone before seemed to be doing well. The stories arrived in waves, everywhere they went – so many stories of wealth and opportunity had to be true, right? Besides, the possibility of escaping lives of poverty and hardship was too alluring to ignore. For generations now, their homeland had been devastated again and again. A century of war had left towns decimated, populations wiped out. The survivors would flee, start again to rebuild their lives, and be wiped out again by another war. Harsh weather and collapsing food supplies would exacerbate the problems some years, only reinforcing their frustration at their marginalization within their culture – beholden to more powerful groups, forced to pay taxes and duties just because of their status. Enough was enough –to America!

They sold everything they had to make the first part of the journey. As they migrated through transit countries, they found themselves stuck, destitute, hungry, with governments unwilling to tolerate their presence. Finally arriving at the border of their destination country, their hope turned to dismay: They were not, in fact, wanted. The warm welcome they expected did not happen. They were crowded into filthy camps. They waited while the government debated what to do with them. Finally, someone in the government came up with a plan: The migrants could be politically useful! Those found unacceptable were sent back to where they came from, but the rest would be transported to the periphery of the country, where they would become someone else’s problem.

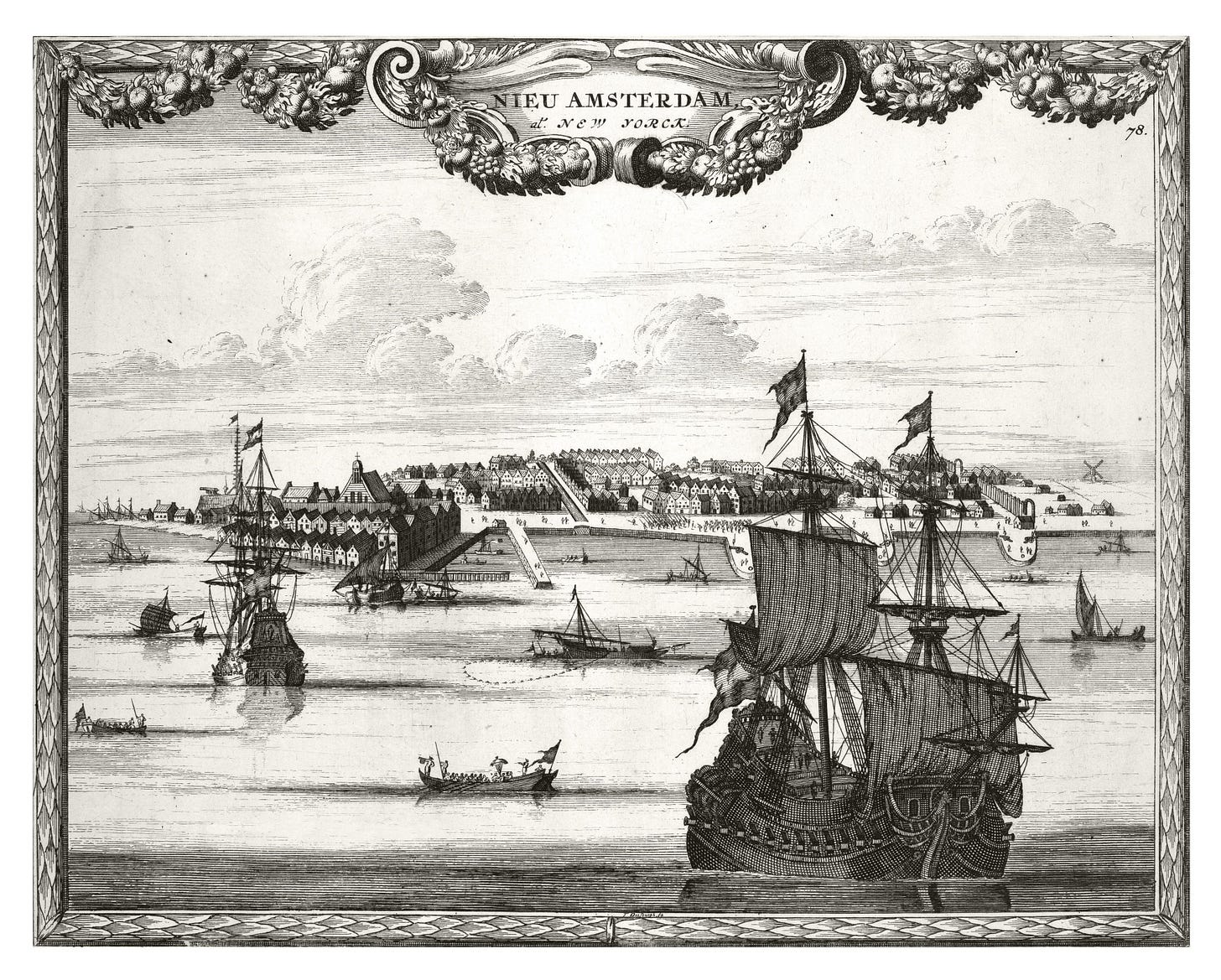

This is a true story. It isn’t about Mexicans or Venezuelans or Haitians. This story describes a wave of immigration from southwest Germany to New York in 1709-10. Those immigrants founded communities in New York, Pennsylvania, and eventually Virginia where future generations of their families and neighbors from southwest Germany would join them throughout the eighteenth century, giving rise to many of the old “Pennyslvania Dutch” communities in British North America. I’m drawing here from a handful of great books and articles on the subject, including this one by Walter Allen Kittle from 1937 and this terrific modern treatment (focusing on the distinct cultural, religious, and geographic identities of the migrants) by Philip Otterness in 2004.

The ”Golden Book”

The rumors started with a book. It had a gold cover and a picture of Queen Anne of England inside. Most people in the Rhineland couldn’t read, but they traveled and talked as they sold the wine that they produced for their livelihoods. Those who could read “the golden book” told of an earlier party who had traveled to England in 1708, where Her Majesty had awarded them land in North America and free passage to get there. The “golden book” the migrants described was probably written by Joshua Kocherthal, a Lutheran minister from south of Heidelberg who had managed to secure support from the Queen for a small settlement in New York, who wrote the book at the urging of proprietors from the Carolinas. A very official-looking letter describing the support given to the 1708 emigrants settled the matter.

In early 1709, thousands of people from around the Rhineland – some but by no means all from “the Palatinate,” as the English would later describe them – suddenly sold their possessions, boarded boats to Rotterdam, and rejoiced at the good fortune that would surely await them when they reached England and Queen Anne’s largesse.

Most of the migrants cited poverty as their reason for leaving, not persecution. While they would have spoken cautiously to the authorities who had to approve of their departure and collect the manumissions they owed for liberation from their feudal obligations, the Palatinate region was highly diverse through centuries of migration, and religious differences were generally tolerated. For a century, however, the region had been at the crossroads of warfare: The Thirty Years War (1618-48), the War of the Palatine Succession (1688-97), and the War of Spanish Succession (1701-14) had repeatedly decimated the populations and property of villages along the Rhine. Doubtless many families despaired of ever finding security and prosperity in such a region.

Transit through the Netherlands and Arrival in England

In Rotterdam, the Dutch couldn’t wait to be rid of them. The British representative to the Hague, however, thought they might be politically useful to Britain: The Whigs, who believed that population growth would lead to national wealth, had recently succeeded in passing a generous new naturalization law to attract immigration, which the skeptical Tories resisted. The Queen eventually was convinced to pay for the migrants’ passage to England, where they might be put to work.

Had it stopped with the first voyage of a few hundred migrants, that might have worked. But people kept coming – more than thirteen thousand people left villages along the Rhine by the middle of 1709. In England, they first crowded into the tenements of St. Catherine’s, but the threat of disease led to their removal to some unused barns south of London, around Blackheath and Camberwell.

As summer drew to fall, the Britains’ attitudes toward the foreigners began to change. Initially sympathetic to their poverty, more observers began to question the migrants’ claims of persecution by the French Catholics (nearly one-third of the migrants were themselves Catholic, it turned out, and many were intermarried). Patience began to wear thin.

Resettling or Removing the Migrants

Something had to be done about these migrants, and soon. With the last Jacobite invasion only a year in the past, the British still feared an invasion of Britain supported by French and Catholic armies. That settled the matter for more than two thousand of the migrants – the Catholics were sent back to their villages in Germany.

The Protestants, however, might have some value for England. The Whig lords in Ireland saw in them the possibility of a Protestant bulwark against the dangerous Irish Catholics. In early September, England transported more than twelve hundred of the Germans to Ireland, though the feudal conditions there so little improved upon the lives they had left in the Rhineland that almost all of them by November managed to find a way back to England.

The British cooked up other plans for settling the migrants. A small group sailed for the Carolinas in January, of which nearly half died on the disastrous voyage, others were killed in Indian warfare, and the rest lost title to their lands for decades. The British Board of Trade suggested sending them to New York, where they might be settled in lands along the periphery of British settlements there, creating a physical (and, implicitly, disposable) barrier to French and Indian invasion. The plan was modified by the colonial governor of New York, who proposed to put the migrants to work producing pitch and tar – necessary components for building and maintaining British Naval ships – to pay for their passage. After their indentures, each person could be awarded forty acres outside the British settlements in New York as insurance against invasion.

Queen Anne approved this plan on January 7, 1710 – but not before the Board of Trade had, in their enthusiasm, chartered ships for the migrants’ passage to North America.

Ripple Effects of the 1709 Migration

I came across this story while doing research for the biography of Wilbur Carr, the mid-level State Department employee who would draft the Immigration Act of 1924 and direct the implementation of the public charge rule against German Jewish refugees in the 1930s. Carr came from a farming community in southwest Ohio, where his maternal great-grandparents had migrated to from the German communities of Pennsylvania and Virginia a few decades after the Palatinate migrants arrived there. Understanding Carr’s story led me to their story.

These Rhineland Germans left for England hoping for large and profitable farms in North America. Their descendants eventually found that in southwest Ohio, where their legacy still exists today. By the Gilded Age, however, city life offered employment opportunities that those ill-suited to farming (like Carr) would leave the farms to explore. The values of those communities, however, shaped generations of their children and, in this particular case, those children shaped our nation’s laws about future generations of immigrants fleeing similar conditions in other countries.

1. Settlers are not migrants. Settlers leave an existing society, usually in groups, in order to create a new community, in a new and often distant territory. Imbued with a sense of collective purpose, they subscribe to a compact that defines the basis of the community they create and their relations with their mother country. Migrants do not create a new society, they move from one society to a different society. 17th & 18th century settlers and conquerors created societies that embodied the cultures and values they brought with them from their origin country, and created a first world civilization.

21st century economic migrants to vast welfare apparatuses first world countries and multi-billion dollar "refugee" resettlement industry are not the same.

2. "Multi cultural" societies are not the end of history, but rather a complete cultural anomaly afforded to certain countries by financial domination of the US led global order.

As the empire rots and recedes, and the elaborate network of printed money and taxes that keeps rival groups placated drys up, conflicts amongst racial and cultural lines will explode. You are seeing this in Denmark.

Not all countries have formal population registers. However, Scandinavian countries in particular are well-regarded in this respect, having government databases storing comprehensive and high-quality data of the full populations. Denmark is especially interesting because it is the only Scandinavian country to have properly quantified the net fiscal impact of immigration based on register data. This analysis has been conducted and described in the official Danish government report, Immigrants’ net contribution to the public finances in 2018. The net financial contribution of a person is conceptually simple: their total contribution to the state finances, subtracted their total costs.

The report finds that the total net contribution in 2018 by native Danish people was +41 billion DKK. The contribution of immigrants and their descendants was net negative at -24 billion DKK (Table b).