Why I’m Writing a Book about “White" People

And why I'll share travelogues from the journey on "How We Got Here"

More than any time since the 1960s, questions of race and racism drive American politics today. George Floyd’s tragic death on May 25, 2020, and the far too many violent deaths of Black Americans since then, underscored but didn’t start the debate. At least since Donald Trump announced the details of his immigration platform on August 16, 2015, race, ethnicity, and racial power reverberate through nearly every political and social issue our country faces.

As an immigration lawyer running a law school clinic, my students and I see these issues and the policies they generate playing out in the lives of our clients as they navigate the legal system. Like many of my students, I became an immigration lawyer because the presidential election of 2016 galvanized me to take a stand against what I viewed as dangerous intolerance. Suddenly, our existing need at WVU Law to fill a vacancy in immigration law offered me an outlet I needed.

Why “Whiteness” Matters

What I don’t hear in our contemporary political or social dialogue, however, is much conscious definition of what it means to possess racial power in this country, to be “White.” To people on the right, perhaps, the definition doesn’t matter, since they often don’t buy it that race determines much anyway. To people on the left, however, Whiteness closely equates with power (whether consciously or unconsciously wielded). But (to paraphrase Catharine MacKinnon), what is a “White” person, anyway?

I’ve written before about my own heritage and how it complicates my identity as a “White” person when it comes to immigration. If this defining of “Whiteness” were merely a matter of personal identity, however, I wouldn’t bore you with it. (I’m a law professor; there are plenty of other things I could bore you with.) And I certainly don’t believe that I or anyone else needs to define “Whiteness” to find some loophole through which to escape some misplaced guilt by association (or, conversely, to define our membership in the power elite).

If the other side is perceived as a dangerous adversary threatening or frustrating identity needs, the common starting place is to draw a line in the sand between Us and Them. Each side feels relatively blameless, and each sees the opponents as aggressive, perhaps even evil.

— Jay Rothmann

Besides, I’m a lawyer, not a social scientist. I became a lawyer because I’m fundamentally pragmatic. Ideas are great, but I don’t want to spend scarce and precious scholarship time on something that doesn’t have the potential to move the law and affect people’s real-life rights and obligations.

But the more I think about it, the more I think understanding “Whiteness” might matter more than anything else for moving immigration law. Over the past eight years, political rhetoric has become shockingly polarized. In a dialogue going on around the clock in Washington and in the 24-hour news cycles of FOX and CNN, each side caricatures and then condemns the purported views of the other while rationalizing or ignoring the failures and inconsistencies of their own positions.

There’s a neurological explanation for all this. As I’ve discussed before, when our opinions on issues like immigration or race relations become “sacred values,” we’re no longer neurologically capable of negotiating trade-offs around them. All the logic in the world won’t change our views.

Instead, we tend to get explosions. Conflict resolutions scholars for decades have described what Terrell Northrup called “identity-based conflicts,” which involve not just disputes over resources but assaults on a person’s or group’s fundamental sense of self. When our “core constructs” get challenged, we feel an intense sense of identity threat. At this stage, we often develop increasingly rigid interpretations of the world, in which the distinction between ‘self’ and ‘not-self’ becomes hardened and the ‘other’ is demonized. Bad motivations are then attributed to the opposing party. As conflict resolution scholar and mediator Jay Rothman wrote, “[i]f the other side is perceived as a dangerous adversary threatening or frustrating identity needs, the common starting place is to draw a line in the sand between Us and Them. Each side feels relatively blameless, and each sees the opponents as aggressive, perhaps even evil.” The subsequent behavior of the other side will likely soon validate our view, since other people will usually respond to our distortions of them by becoming more distortive of us. And the cycle continues.

I love the show “Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates Jr. ” because it demonstrates, week after week, how our conscious identities vastly oversimplify the complex realities of American (and, really, human) history. Only by uncovering that complexity can we begin to soften the rigid interpretations that nearly all of us have developed of the world and each other, and potentially sidestep the types of intractable conflicts that conflict-resolution scholars specialize in — conflicts that in many cases have persisted for millennia with no sign of resolution, and no winners.

Biography of a “White” Man

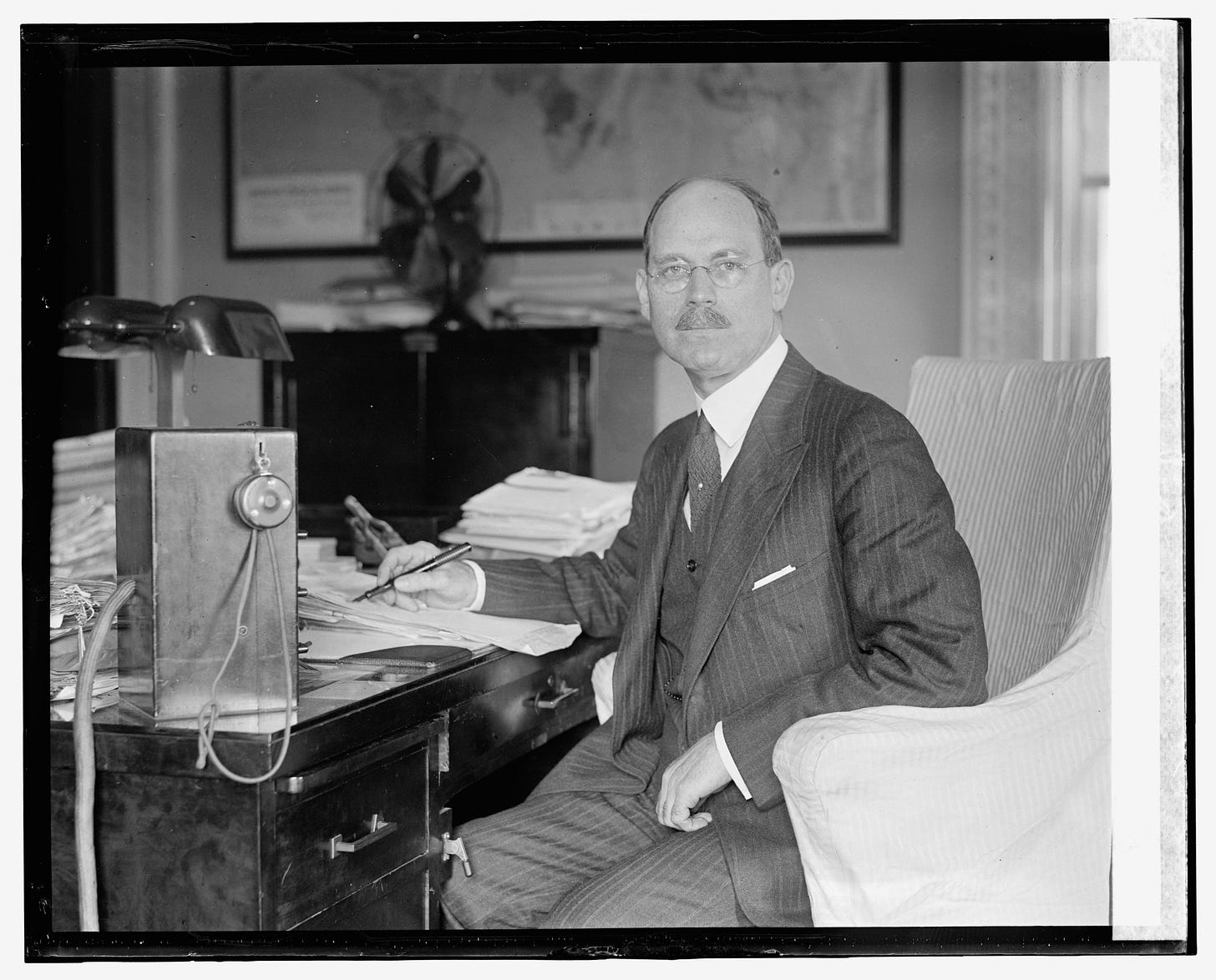

To explore the complexity of “White” identity, I’ve found myself drawn (almost unwillingly, like a moth to a flame) to the life and papers of a mid-level State Department bureaucrat named Wilbur J. Carr. At first I couldn’t explain why. As a historical figure, he turns up mostly in inquiries about whether anti-Semitism explains American delay in protecting Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. Though the Library of Congress houses volumes of his journals and papers, no modern scholar has written much about him.

Most of us, like Carr, just want to get to work on time, do a good job, feel valued, and have some free time to spend with people and hobbies we love. To what extent do those decisions – conscious and unconscious – shape the course of history? To what extent does history actually shape us?

Reading his journals, I can see why. By himself, Carr was boring. State valued him as an administrator, not a policymaker. His journals focus on the mundane: The price of train tickets, the hours he worked, the appointments he kept, when he found time to play the mandolin — in short, the kinds of details that make up most of our lives, most of the time.

So why couldn’t I stop reading his papers? Something, I realized, fascinated me about this relatively ordinary man who ended up in extraordinary circumstances that he didn’t (by his own private admission) fully appreciate. Most of history has been written about “great men” — those extraordinary (for good or ill) individuals whose actions decisively turned the course of events. But those “great” men don’t act alone; they act mostly through the work of hundreds or thousands of “ordinary” people.

And most of us aren’t “great.” Most of us, like Carr, just want to get to work on time, do a good job, feel valued, and have some free time to spend with people and hobbies we love. To what extent do those decisions — conscious and unconscious — shape the course of history? To what extent does history actually shape us?

Eventually, I realized that Carr’s life fascinated me as a window into the meaning of “Whiteness” in the sense of social and political power in American history. Carr would qualify, today, as a “White” man. His father’s family came from England and fought in the Revolutionary War; his mother’s family fled hardship in Germany and, a couple of generations later, settled in the Ohio farm community where many Carrs and Fenders still live today. Carr himself traveled from that Ohio farm to the State Department and eventually to the ambassadorship of Czechoslovakia against very long odds, and he felt a sense of inferiority to the Brahmins around him at the State Department.

Almost universally, the people who knew Carr appeared to respect or even love him for his reliability, his equanimity, his gentleness. For his day, he was a Reformer. He also played a pivotal role in defining who was not “White” enough to enter the country under the Immigration Act of 1924 and how few European Jews would find refuge in the U.S. in the years before World War II.

Conveniently, his life spanned almost precisely the era in which our immigration legal system emerged, ending before the full horror of the Holocaust had been revealed. Had we walked in precisely his shoes from his birth in rural Ohio in 1870 until his death in Baltimore in 1942 — seeing only what he saw and knowing only what we knew — would we have understood better? Would we have acted differently?

Finding the Story: Subscribe to Get Weekly Reports from the Time Traveler

Having completed much of my foundational research, this year I’ll start focusing in earnest on finding and writing Carr’s story. On How We Got Here, I’ll share what I’ve learned each week — surprising lessons from the archives; frustrations of trying to follow dusty footsteps a century old; insights and conundrums into what “Whiteness” might mean as seen through Carr’s life. From time to time, I’ll share excerpts from the book draft for your reactions.

By walking in the shoes of this man whose identity afforded him the power to define “Whiteness” for others, I hope not exactly to change our view of what “Whiteness” means, but to deepen our understanding of the complexity of that identity and, with that understanding, to deepen our empathy for our shared humanity — in all its beauty and ignominy.

With greater empathy, perhaps we can start to soften our rigid interpretations of our immigration laws, the people who made them — and, most importantly, the people who disagree with us about them today. Only from that softer starting point do I feel any hope of achieving comprehensive immigration reform, or even beginning a rational dialogue toward it.

As Arthur Brooks is fond of saying, this isn’t research; it’s me-search — I’m writing this book about Carr because I need to take this journey through the last century and a half of American immigration legal history in order to shake loose from my hardened perspective about immigration law and policy.

I hope there’s something in this story that speaks to a need in you as well. If so, you can subscribe to get weekly reports from your intrepid time traveler. I see this space on How We Got Here as a forum for working out ideas about what I’m finding and seeking your perspectives on those discoveries. Is there something you’d want to explore more deeply about the events or the culture? A perspective I’ve overlooked in interpreting them? Let me know in the comments, and I can write the book you want to read, too.

Lots of intriguing points and concerns raised here. My approach will be to explore those ideas through a close-up view of one particular man. I don't really aim to "educate" anyone so much as to take an empathetic but unsentimental look at one complete life that was lived in the context of these questions. Hopefully anyone who reads it comes away aware of these and other complex questions and deepens their own perspective.

Joe, you bring up some really good points. My questions are similar and have to do with assimilation. Regardless of what the color/culture of a state is originally, too much immigration without assimilation is dangerous for all. The laws are designed based on the cultural norms of those that wrote them. Add a new group of significant size and there is discontent, even violence on all sides. I think any immigration policy must be structured around assimilation. Ironically, one thing that seems to foster assimilation is intolerance.